Fiber Guide

The Importance of Fiber in Functional Medicine

Fiber is one of the most underrated yet foundational nutrients in functional medicine. While it’s often talked about simply in terms of digestion or regularity, fiber plays a far deeper role in gut health, immune regulation, blood sugar balance, hormone detoxification, and overall metabolic health.

What Is Fiber?

Fiber is a type of carbohydrate found in plant foods that the body cannot fully digest. Instead of being broken down and absorbed like other carbs, fiber travels through the digestive tract, supporting digestion and feeding beneficial gut bacteria.

There are two main types of dietary fiber: soluble and insoluble, and both are essential for optimal health.

How Much Fiber Do We Really Need?

Most people fall significantly short of the recommended fiber intake. While general guidelines suggest 25–38 grams per day, functional medicine emphasizes individual tolerance. Many experts recommend 30-50g of fiber daily.

If you’re healing the gut or dealing with bloating, IBS, or dysbiosis, fiber should be increased slowly and strategically, often starting with well-tolerated soluble fibers before layering in more insoluble sources.

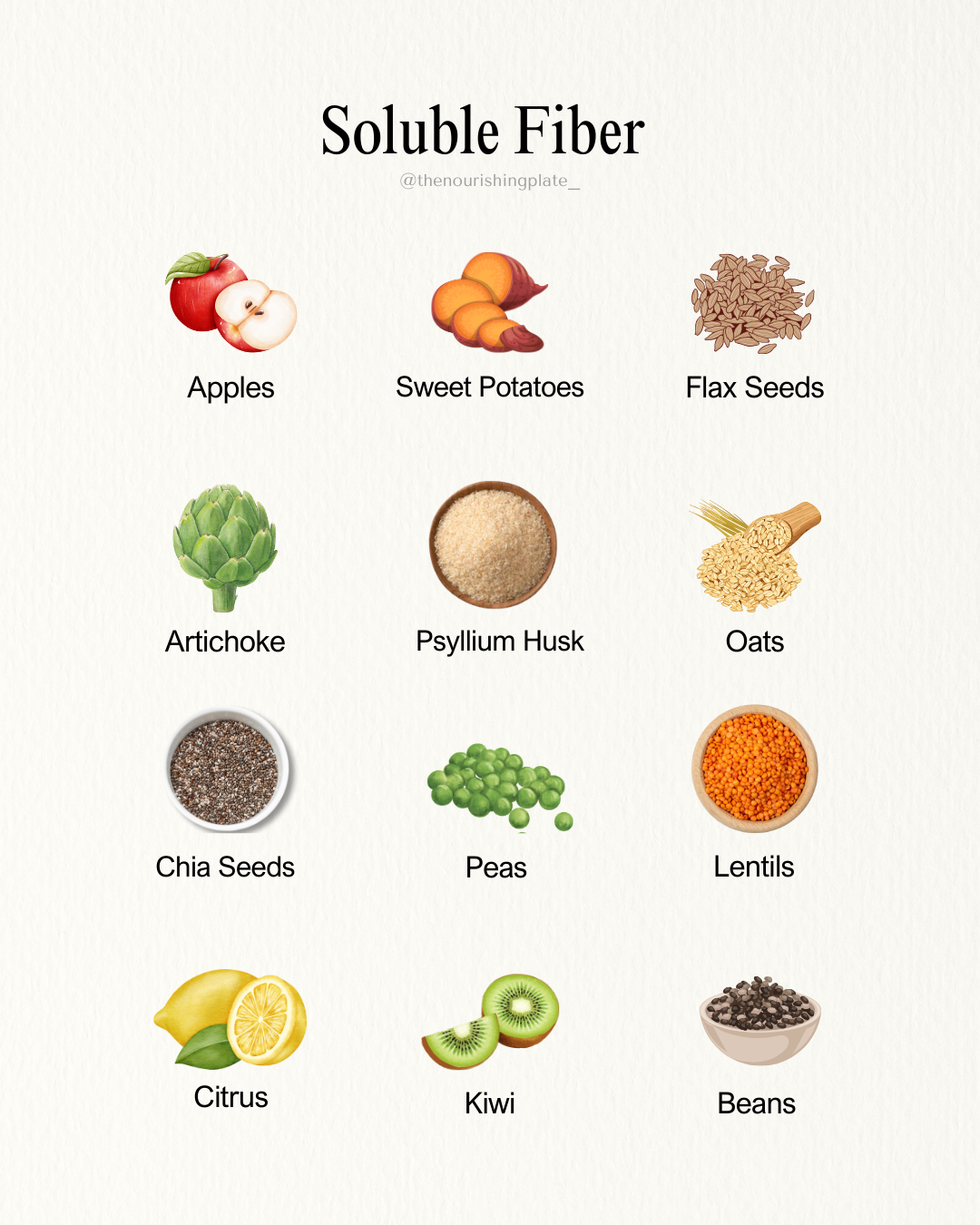

Soluble Fiber: Fuel for Gut Bacteria

Soluble fiber dissolves in water and forms a gel-like substance in the gut. This type of fiber is especially important in functional medicine because it acts as a prebiotic, feeding beneficial gut bacteria.

When gut bacteria ferment soluble fiber, they produce short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) such as butyrate, acetate, and propionate. These compounds:

Strengthen the gut lining

Reduce inflammation

Support immune health

Improve insulin sensitivity

Play a role in brain and mood health via the gut-brain axis

Foods High in Soluble Fiber

Oats

Chia seeds

Flaxseeds

Beans and lentils

Apples

Citrus fruits

Carrots

Sweet potatoes

Psyllium husk

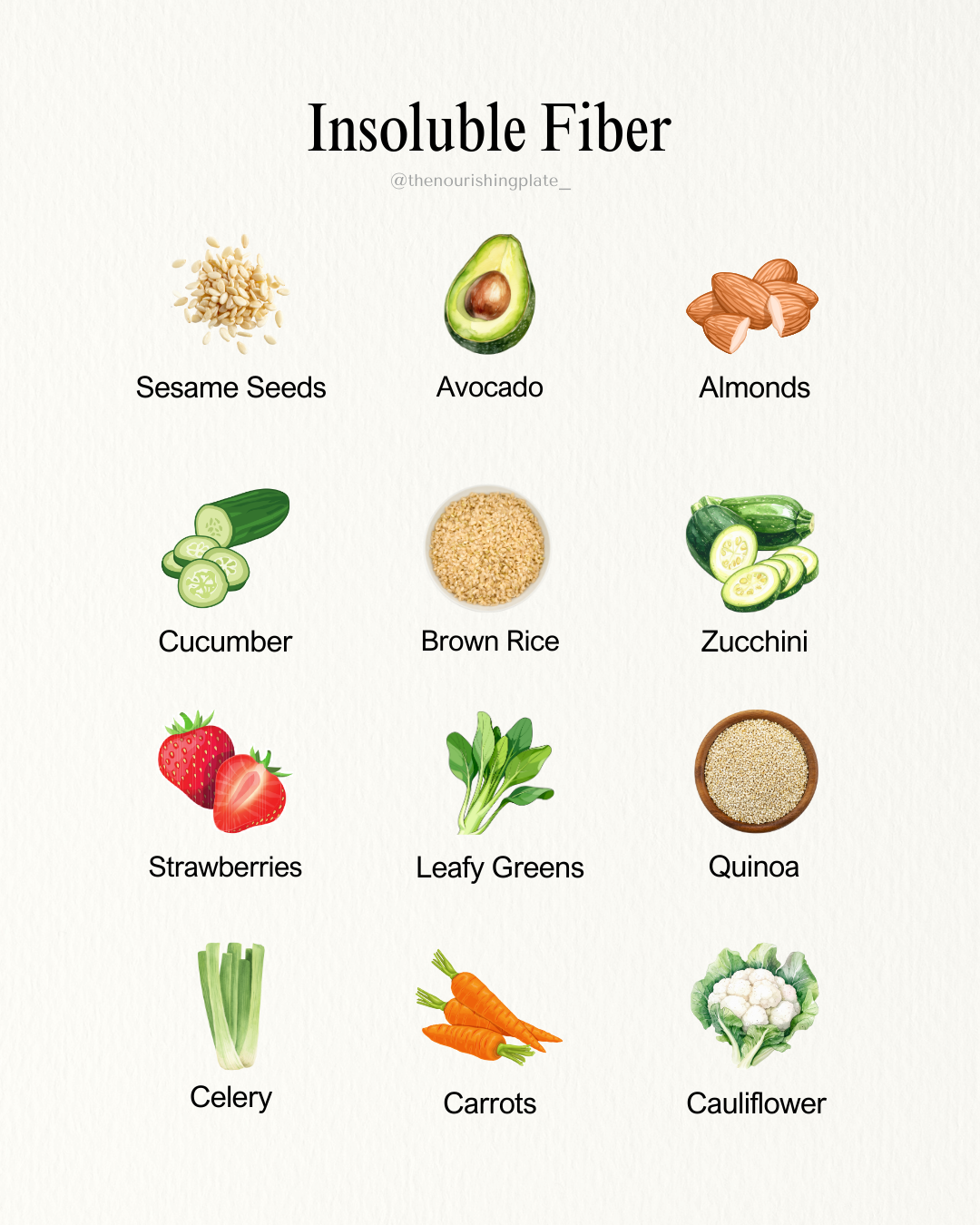

Insoluble Fiber: Supporting Motility and Detoxification

Insoluble fiber does not dissolve in water. Instead, it adds bulk to stool and helps move waste through the digestive tract more efficiently. From a functional medicine perspective, this is crucial for detoxification and hormone balance.

When stool moves too slowly, toxins, excess hormones (such as estrogen), and metabolic waste can be reabsorbed back into the body. Insoluble fiber helps prevent this by promoting regular, complete bowel movements.

Foods High in Insoluble Fiber

Leafy greens

Cruciferous vegetables (broccoli, cauliflower, Brussels sprouts)

Nuts and seeds

Whole grains (when tolerated)

Zucchini

Green beans

Bell peppers

Celery

Fiber and Gut Microbiome Diversity

One of the most powerful roles of fiber in functional medicine is its impact on gut microbiome diversity. A diverse microbiome is associated with:

Lower inflammation

Better immune resilience

Improved digestion and nutrient absorption

Reduced risk of metabolic and autoimmune conditions

Different types of fiber feed different strains of bacteria. Eating a wide variety of plant fibers, often referred to as “eating the rainbow,” helps cultivate a resilient and diverse gut ecosystem.

Low fiber diets, especially those high in ultra-processed foods, are strongly associated with dysbiosis (imbalanced gut bacteria), constipation, bloating, blood sugar instability, and chronic inflammation.

Fiber’s Role Beyond the Gut

In functional medicine, we also look at how fiber impacts systems beyond digestion:

Blood Sugar Balance: Fiber slows glucose absorption, reducing blood sugar spikes and crashes.

Hormone Health: Fiber binds excess estrogen in the gut, supporting proper hormone clearance.

Cholesterol Regulation: Soluble fiber helps bind cholesterol in the digestive tract.

Immune Function: A healthy gut microbiome (fed by fiber) regulates up to 70% of the immune system.

Key Takeaway

Fiber is not just a digestive aid it is a cornerstone of functional medicine. By nourishing beneficial gut bacteria, supporting detoxification, stabilizing blood sugar, and reducing inflammation, fiber helps create the internal environment needed for healing.

Prioritizing a wide variety of fiber-rich whole foods is one of the most powerful and accessible steps you can take toward long-term gut and whole-body health.

References

Anderson, J. W., Baird, P., Davis, R. H., Ferreri, S., Knudtson, M., Koraym, A., Waters, V., & Williams, C. L. (2009). Health benefits of dietary fiber. Nutrition Reviews, 67(4), 188–205. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1753-4887.2009.00189.x

Cronin, P., Joyce, S. A., O’Toole, P. W., & O’Connor, E. M. (2021). Dietary fibre modulates the gut microbiota. Nutrition, 92, 111394. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nut.2021.111394

Makki, K., Deehan, E. C., Walter, J., & Bäckhed, F. (2018). The impact of dietary fiber on gut microbiota in host health and disease. Cell Host & Microbe, 23(6), 705–715. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chom.2018.05.012

Slavin, J. L. (2013). Fiber and prebiotics: Mechanisms and health benefits. Nutrients, 5(4), 1417–1435. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu5041417

Stephen, A. M., Champ, M. M. J., Cloran, S. J., Fleith, M., van Lieshout, L., Mejborn, H., & Burley, V. J. (2017). Dietary fibre in Europe: Current state of knowledge on definitions, sources, recommendations, intakes, and relationships to health. Nutrition Research Reviews, 30(2), 149–190. https://doi.org/10.1017/S095442241700004X

U.S. Department of Agriculture & U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2020). Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2020–2025. https://www.dietaryguidelines.gov

Valdes, A. M., Walter, J., Segal, E., & Spector, T. D. (2018). Role of the gut microbiota in nutrition and health. BMJ, 361, k2179. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.k2179

Weickert, M. O., & Pfeiffer, A. F. H. (2018). Impact of dietary fiber consumption on insulin resistance and the prevention of type 2 diabetes. Journal of Nutrition, 148(1), 7–12. https://doi.org/10.1093/jn/nxx008